Rite of Spring

- Choreographer: Nicolas Petrov (1972, 1974); Glen Tetley (2001);

- Music: Igor Stravinksy

- Costumes: Henry Heymann (1972, 1974); Nadine Baylis (2001);

- Lighting: John B. Read, Pat Simmons (1974)

- Set Design: Nadine Baylis

- World Premiere: Bavarian State Opera, April 17, 1974

- PBT Performance Date: April 7 & 9, 1972; March 22-24, 1974; May 10-13, 2001;

Program Notes

Program Notes (May 2001)

By Carol Meeder, former Director of Arts Education

Original Premiere: Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, Paris Opera Theatre, 1913. Choreography by Vasla Nijinsky. Design by Nicholas Roerich.

Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Premiere: Heinz Hall, 1972. Choreography by Nicolas Petrov. Design by Henry Heymann.

From its premier on May 29, 1913 at the Theatres des Champs-Elysees in Paris to its most contemporary performances, The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky has inspired a primitive, primal reaction from its audience and its choreographers. Its magnetism has challenged more than forty-five twentieth century choreographers to tackle its theme

For several years Stravinsky had been planning to write a “musical-choreographic” work that would depict an ancient Russian pagan myth representing the mystery and surge of the creative power of spring; “the violent Russian spring” that Stravinsky loved; the one “that seemed to begin in an hour and was like the whole earth cracking.” He collaborated on the original scenario with the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich who was also an authority on pagan Russia. The basic structure would be the Awakening of Nature to the thawing earth, the Adoration of the Earth with its primitive fertility rites initiated with the coming of Spring, and “the climax was to be a solemn ritual in which a maiden danced herself to death to propitiate the god of spring.”

When approached with this scenario Serge Diaghilev convinced Stravinsky to write a ballet, not just a symphonic piece. In her book, Sacre du printemps – Seven Productions from Nijinsky to Martha Graham, Shelley C. Berg writes, “For Diaghilev it was the consummate synthesis, an extraordinary opportunity to bring together the ancient world of Slavic myth and ritual and the modern sensibility and power represented by Stravinsky’s music. If it was primitive barbarism Europe really wanted, they would have it with Sacre du printemps.” It was part of the neo-nationalistic movement in Russia, which dovetailed with the increasing fascination of Western Europe with the exoticism of all things “russkii.”

The third member of the creative triumvirate that produced Le Sacre du printemps for its premier with Serge Diaghilev‘s Ballets Russes was Vaslav Nijinsky. Although known mostly for his legendary dancing, it was his choreography that exploded that night in Paris. As Stravinsky’s score strayed from traditional melodies and harmonies to one that was dominated by complex rhythms with visceral power, so did Nijinsky’s choreography stray from all preconceived notions of what ballet should be.

Bronislava Nijinska, Vaslav’s sister and a dancer/choreographer in her own right wrote of her brother’s choreography –

“the men in Sacre are primitive. There is something almost bestial in their appearance. Their legs and feet are turned inwards, their fists clenched, their hands held down between hunched shoulders; their walk on slightly bent knees, is heavy as they laboriously straggle up a winding trail stamping in the rough, hilly terrain.

The women…are also primitive, but in their countenances one already perceives the awakening of an awareness of beauty. Still their postures and movements are uncouth and clumsy as they gather in clusters on the tops of small hillocks and come down together to meet in the middle of the stage and form a large crowd.”

The premier of this work has gone down in history as one of the legendary events in musical and ballet performances. It was so revolutionary and scandalous that a riot broke out in the theater. After the performance both Stravinsky and Nijinsky fled the theater while the audience, divided on their reactions, carried on the melee. Francis Poulenc (composer of Concerto in G Minor for Organ, Strings, and Timpani, the musical score for Glen Tetley’s Voluntaries) was in the audience that evening. He was fourteen years old at the time and witnessed an elderly Comtesse de Pourtales screaming that she was being taken for a fool by the performance while composer Maurice Ravel kept shouting, “Genius!” There were only nine performances completed amid the controversy, but merely one year later, in the same city, the concert version of The Rite of Spring received a standing ovation.

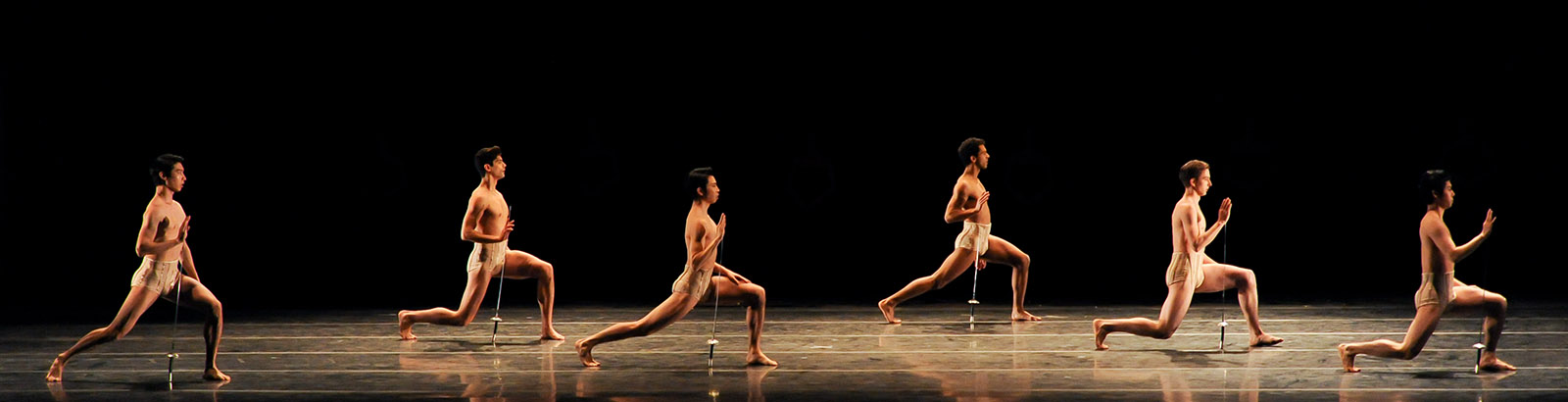

Glen Tetley’s contemporary production of The Rite of Spring was originally created for the Munich Ballet in 1974 and has been restaged for many other companies. Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre’s production employs the sets and costumes created by Nadine Baylis for the re-staging at the National Ballet of Canada in 1993. Tetley has brought his personal choreographic language to this production. Although it shares the inspiration of the compelling musical score with other versions, Glen Tetley, as always, imprints the production with his signature.

Unlike the original and many other productions, Tetley has cast a man in the leading role of the Chosen One or victim of the rite. English critics Mary Clarke and Clement Crisp write that the theme of Glen Tetley’s Sacre is “the sacrifice of a chosen youth who is the incarnation of men’s hope and sins and sufferings. He is killed as a scapegoat, but is reborn with the spring and represents the hope and promise of a new life…In a final coup de theatre he is whisked heavenward in an explosion of energy.” His choreography reflects the vitality and driving force of Stravinsky’s music maintaining the passion and dynamic pulse that precipitated that scandalous premier. Appropriate to the earth related theme, the women are clad in flat ballet slippers rather then pointe shoes. The Rite of Spring was one of the first works that Tetley created for a large cast of dancers and was the precursor of many of his large ensemble pieces, among them, Voluntaries.

In its infancy Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre first staged The Rite of Spring in 1972. It was part of “an Homage to Stravinsky” produced by PBT’s first artistic director Nicolas Petrov. With Petrov’s choreography the ballet was set for eighty dancers, among them our current ballet master Roberto Munoz who danced to the strains of the challenging score, provided by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. As PBT performed The Rite of Spring at its birth and now, as it continues to mature, it is part of the continuing journey of an art. The Dance Critics Association writes that, “The premiere of The Rite of Spring has often been described as the birth cry of modernism – and the rage of the audience as an apt response to the unveiling of twentieth century art, so drastic and comfortless. By this argument, The Rite of Spring is the very prototype of the modern.”