Airs

- Choreographer: Paul Taylor

- Music: G. F. Handel

- Costumes: Gene Moore

- Lighting: Jennifer Tipton

- World Premiere: Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1978

- PBT Performance Date: May 110-13, 2001;

Program Notes

By Susan McGuire, Repetiteur

Paul Taylor initially began to choreograph Airs to music by Sibelius, on American Ballet Theatre. After several rehearsals he realized that time constraints as well as lack of familiarity with the dancers would make the project unfeasible and was forced to abandon it.

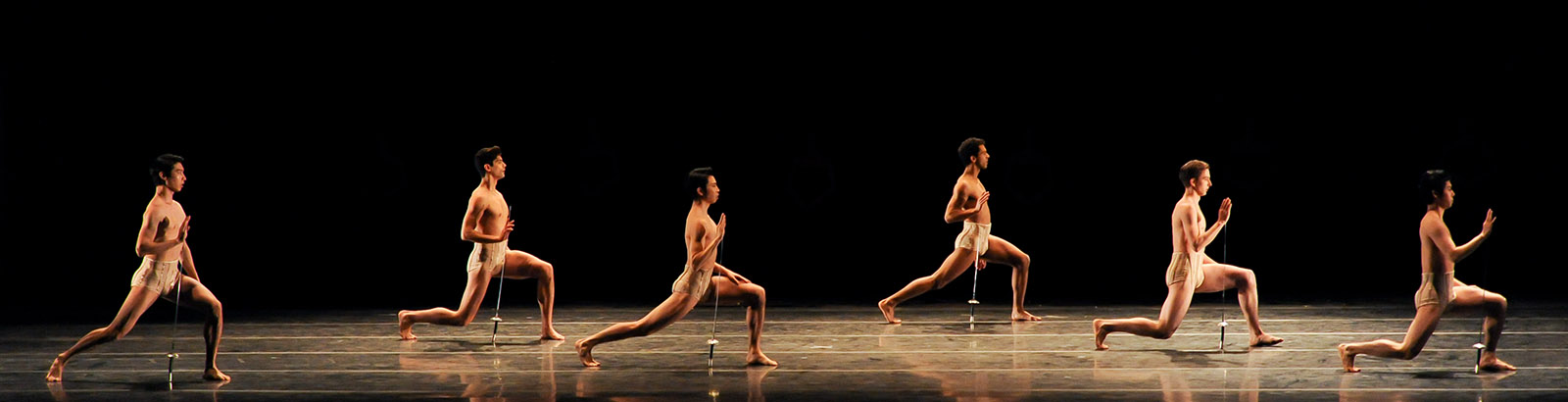

In 1978 he began Airs again, with his own company, using some of the same movement material, to music by Handel. The original title was Windward, which reflected images of air and water currents. The dancers’ movements and spatial patterns suggest gusts, eddies, and an inevitable flow of energy from shape to shape and from dancer to dancer.

The opening section suggests the ebb and flow of the tides with its softly swirling patterns and subsequent calm as the movement subsides. In the second section the women are lifted high into the air and then lowered into swift spirals of movement as the group runs in and out of increasingly complex patterns. The many jumps are buoyant and light, and suggest water splashing, sparkling, into the air. In the third section, an adagio solo on a long diagonal, the dancer sways from one spacious shape to another, suggesting the slow, heavy movement of deep water on the verge of turbulence.

This section leads to a sprightly gigue, in which jumps spring from deeply bent knees, or skim over the surface of the stage like a bird over the surface of the sea. The following quartet, again an adagio, suggests a deep calm. The movement is linear but fluid. Shapes are clear and pure, but flow into and out of each other, and soft, fluid runs join the movement phrases in a seamless pattern that suggest clouds and their constantly changing shapes. This section leads to a swift sextet, with whirl pooling runs and buoyant leaps for the men. One couple continues in a fast duet that twines and untwines, the pair never disengaging, with lifts that spiral high into the air. Immediately following, the couple repeat the movement almost verbatim, but in slow motion. The duet now suggests resolution, or the calm after a storm. The penultimate section is brisk and lively, with the cast darting in and out of patterns, air borne one moment and whirling into and out of the floor the next, like a flock of birds touching down for a moment and then rising into the air. The final movement begins with a slow quartet for the women. One by one the men enter, and each gently guides a woman out of the quartet until a solo woman is left to finish the movement. The cast returns to gather behind her as the curtain falls.

In Airs, as with many of his dances, Taylor has chosen to use an arrangement of sections of music rather than one single composition. In spite of the fact that he does not read music, he has an uncanny ability to match the dominant key and instrumentation of one musical section to another. Taylor feels most comfortable working with the Baroque

composers, for the formal structure of the music clearly matches his own sense of craft. Not every dance that he has choreographed to the Baroque composers is as classical in terms of its movement style and lyricism as Airs, however. The masterpiece Esplanade, for example, is based solely on pedestrian movement, consisting of nothing more than walking, running, sliding and falling. But it has an extraordinarily complex and tightly woven structure, and a joyousness and optimism that perfectly suit Bach’s music.

The very classicism, formality and lyricism of Airs has tempted people to think of it as “balletic”, and indeed the dance does incorporate ballet vocabulary, as well as demanding articulation and line from the dancer. Clearly dancers who have had no ballet training would not be able to do it justice. On the other hand, the feeling of weight and fluidity, as well as the ability to travel at speed, seamlessly weaving in and out of constantly shifting and spiraling patterns, is very difficult for dancers trained primarily in ballet, with its emphasis on the vertical and its pin-point balances, to acquire. However, once they have mastered these underlying principles and added to them the clarity and amplitude of movement that ballet training has given them, they are able to bring to Airs a very special beauty of their own.

Since its creation, Airs has gone into the repertory of many ballet companies around the world, including the Royal Danish Ballet, Ballet Rambert, the Birmingham Royal Ballet, and American Ballet Theatre.